Women’s health and gender inequalities – 25 years on from Beijing

1 December 2020

The BMJ has recently published a Collection on Women’s Health and Gender Inequalities. Nick Hooton of ReBUILD for Resilience reflects on some of the key messages shared at the launch meeting for this new collection, at a session of the recent World Health Summit 2020.

In 1995, at the Fourth World Conference on Women, governments from around the world agreed on a comprehensive global plan to achieve equality for women. Known as the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on Women, this was a landmark global policy framework to promote the human rights of women and girls and gender equality. The principles in the plan were also identified as a prerequisite for women’s health and wellbeing.

Now, 25 years later, the BMJ has published a new Collection on Women’s Health and Gender Inequalities, which was launched at a session of the recent World Health Summit 2020. The session (which you can watch on YouTube) highlighted that, despite important progress in the past 25 years, gender discrimination, bias and inequalities in women’s health persist. There are also new and emerging threats to women’s health, including a number highlighted during the current COVID-19 pandemic. The launch meeting included descriptions from three of the initial papers in the Collection, and whilst these covered different topics, there were a number of common themes.

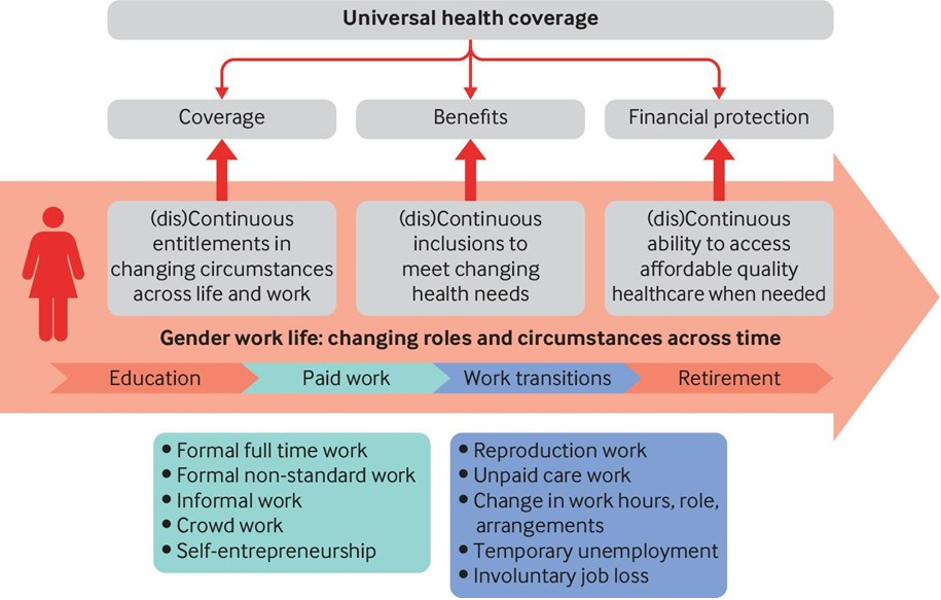

Fig 1: Gendered work trajectories and continuous universal health coverage. Image use courtesy of Lavanya Vijayasingham. BMJ 2020;371:m3384

In many countries in the world, healthcare access is frequently linked to employment-based health financing schemes. But a paper authored by Lavanya Vijayasingham and colleagues (read it on the BMJ website) stresses that health financing and entitlement systems linked to employment can disadvantage women. Whilst the core elements of universal health coverage (coverage, benefits and financial protection) are often included in such schemes, there are structural reasons why women are disadvantaged in all of these elements, reflecting the changing roles and circumstances of women’s employment across time (outlined in the above image which is taken from the paper). Some solutions are proposed, including the delinking of health entitlements and direct contributions, and that parallel schemes should aim to deliver health access in equal quality, benefits and financial protection. More generally the authors argue that UHC design and policy reforms must include addressing gender biases and discrimination, such as in differential benefits packages and valuing unpaid care work more strongly in financial protection and benefit design.

Outlining her paper on violence against female health workers, Asha George used the ‘tip of the iceberg’ metaphor to show the critical importance of understanding the diverse underlying power relation issues which influenced the gender biases and inequalities, which in turn led to actual violence against female health workers. The key messages from the paper are that violence against female health workers is an extreme form of abuse of power within the health workforce and that it is necessary to deal with the underlying gendered power dynamics in order to deal with this violence. Acknowledging, respecting and protecting the rights of women delivering healthcare is essential for the achievement of good quality healthcare worldwide.

Looking at progress since the 1995 Beijing Declaration, Dr Claudia Garcia-Moreno argued that whilst there has been a lot of progress, this was uneven and pockets of inequality remain. For example, maternal mortality was still a major cause of preventable death, HIV infections were still highest amongst young women, and reproductive rights remain contentious despite progress. She also stressed that a lot of women’s health issues were still affected by underlying gender inequalities, at structural level as well as individual, and that despite much more awareness of intersections with other factors, these still need more attention. However, there are opportunities for further progress represented by global and local movements. And the COVID pandemic, as well as its obvious challenges, represents an opportunity to build on innovations which have been necessary to build on access to quality, gender and non-discriminatory services for all women globally.