Can climate finance make a major contribution to funding health system resilience?

10 July 2024

In a recent ReBUILD for Resilience webinar (watch it here), Oxford Policy Management (OPM) presented some of their practical experiences of strengthening climate resilient health systems in Africa and Asia. The role and potential of climate finance (grants, loans and other financial resources for tackling climate change) was a common thread across the presentations and a hot topic of discussion amongst the respondents. In this blog post, Elizabeth Gogoi, a Principal Consultant in OPM’s Climate, Resilience and Sustainability practice, provides some of the highlights of this discussion.

(NB All links open in a new tab)

About USD 1,265 trillion of climate finance was disbursed across the world in 2021/22 (see Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023). This was mainly used for decarbonizing energy systems, transport and buildings and infrastructure.

There is no comprehensive tracking of the proportion of climate finance that supports the health sector (data is available for bilateral flows of climate finance, for which 3% was tagged to ‘health’ in 2018. See Financing for the future). However, one-off studies give some idea of the numbers involved. For example, an estimated USD 1.4 billion of bilateral and multilateral adaptation finance between 2009-19 was committed to the healthcare sector, including projects focusing on infectious diseases, health systems and disease surveillance. Nearly 60% of this was provided by three sources: the EU institutions (USD 373 million), the Green Climate Fund (USD 314 million) and the United States (USD 167 million). 99% of the financing was provided as grants.

In contrast, the health sector received USD 39.2 billion of non-climate related overseas development assistance from bilateral and multilateral sources in just a single year (2022) (See Alcayna, O’Donnell & Chandaria, 2023). In short, relatively little climate finance is finding its way to support the healthcare sector.

Given that the volume of climate finance available to health systems now looks small, is it worth considering?

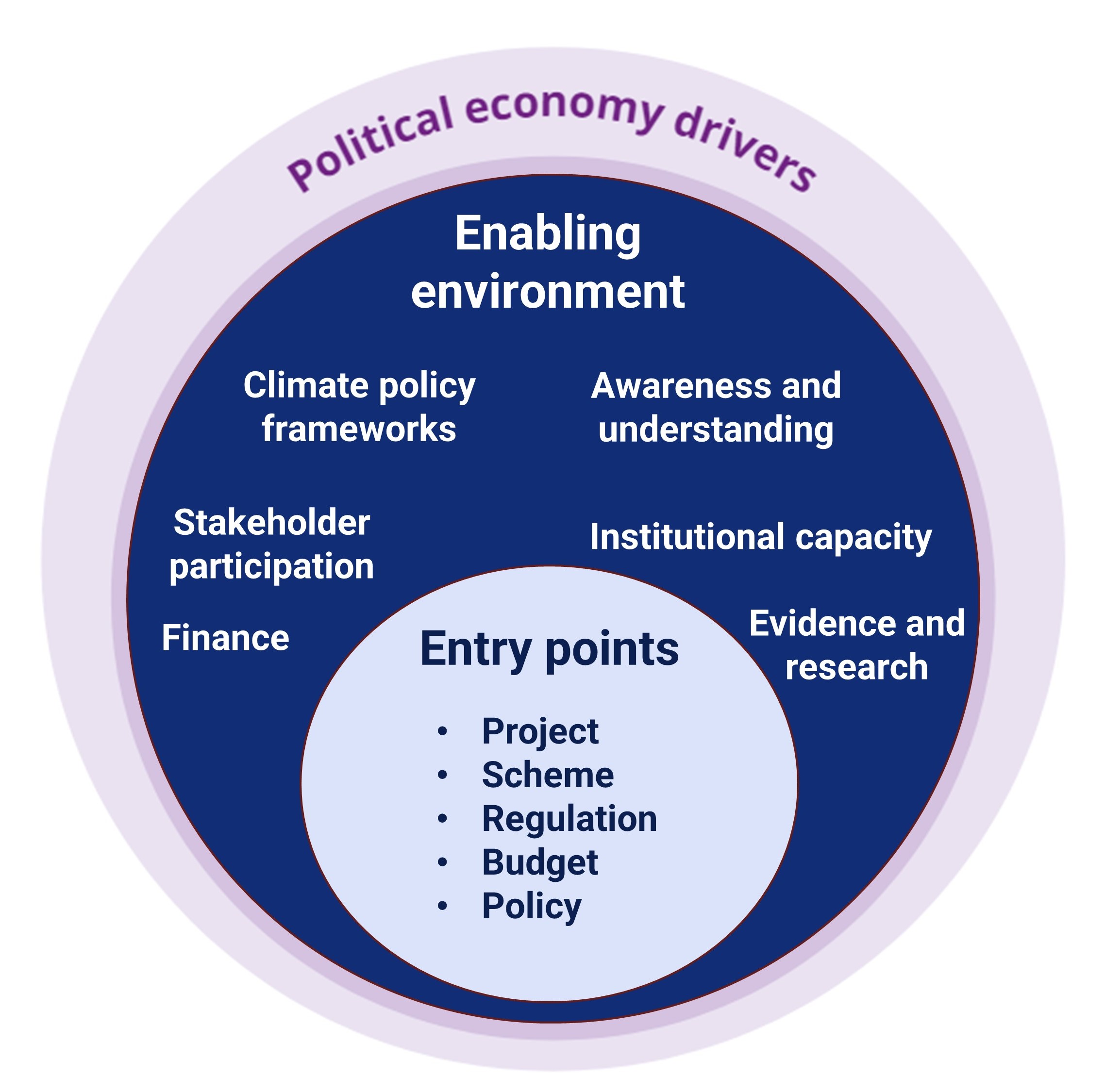

Figure 1. An OPM framework for mainstreaming climate across sectors (a text version of this diagram is available here)

One of the key building blocks to mainstreaming climate change within health system policy and practice is access to finance. I presented (see slides 6-14) a framework we developed for mainstreaming climate across sectors (see figure 1) that includes finance as a key enabler. However, health systems in fragile settings are often already stretched to the limits (see OPM’s previous webinar on public financial management of the health sector), with little flexibility and space in the budget to cover additional costs associated with making health sector infrastructure and services more resilient.

Dr Mahwish Hayee from OPM Pakistan highlighted this reality in a presentation (see slides 15-26) summarizing the findings of our scoping study and framework of action for climate resilient health systems in Pakistan. The need to access new sources of finance was a key priority, with climate finance identified as a potential opportunity.

In the final presentation (see slides 27-38) from OPM, Kenneth Ene unpacked exactly how climate finance could be used, using the specific example of building the resilience of public health facilities.

Kenneth presented analysis we prepared for SEforAll (see Climate Finance for Powering Healthcare) which covered a sample of technologies that could make a facility more resilient to extreme weather events and climate trends. These include off-grid solar systems and solar lanterns (both of which protect facilities from electricity blackouts), and energy efficient and resilient building designs (e.g. cool roofs to reduce indoor temperatures).

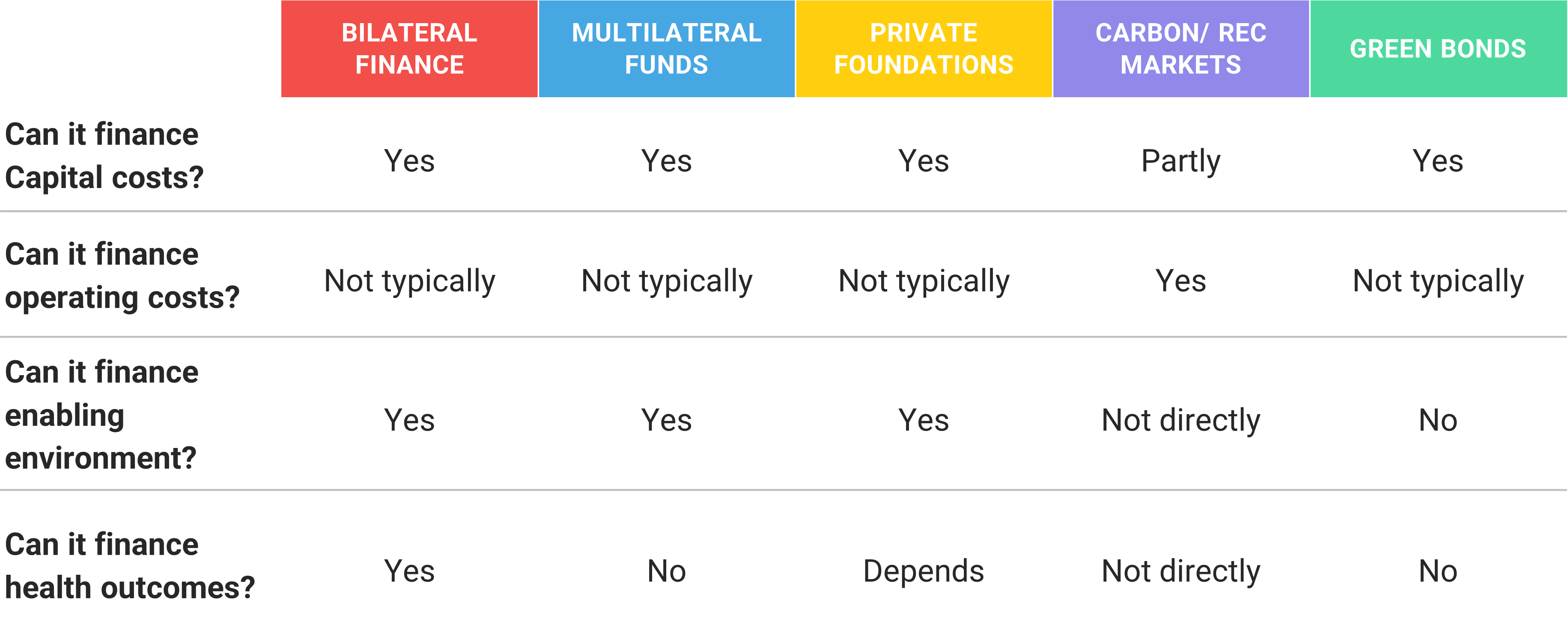

We estimated the scale and type of financing required (e.g. upfront capital costs, ongoing maintenance costs, wider institutional capacity strengthening costs) and explored which sources of climate finance could cover what. This included sources such as global climate funds eg the Green Climate Fund, and bilateral and multilateral development finance that has been earmarked for climate change, as well as private foundations, carbon markets and green bonds. Figure 2 gives a snapshot of the track record of each and potential to finance resilient health systems for each of these sources.

Figure 2. Summary of what ‘type’ of costs related to climate proofing healthcare facilities can be covered by different sources of climate finance (a text version of this table is available here)

The potential of climate finance for health systems

The presentations and discussion that followed highlighted a few key points of agreement amongst the participants on the role and potential of climate finance for health systems in fragile settings.

First, climate finance is not the ‘solution’ to the underfunding of public health systems in low-income or fragile countries. As emphasized by Helen Yaxley from the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, climate finance should complement, not replace, core health systems strengthening efforts and funding.

Second, despite the continued importance of dedicated health system funding and despite climate finance offering relatively small volumes of funding, it still presents an opportunity. Climate finance can provide some flexible financing that allows governments and partners to innovate and pilot new approaches to building resilience. It is also intended to crowd in and catalyze much larger sources of long-term financing.

Third, some resilience building ‘solutions’ are better suited to climate finance than others. For example, strengthening the resilience of health facility infrastructure often requires upfront investments, such as new technology. This makes it more straightforward to calculate the ‘additional’ costs associated with tackling climate change – and it is often only these additional costs that can be covered by climate finance.

Fourth, climate finance should be seen as one of multiple sources of short- and long-term financing. A blended model that uses climate finance to complement or generate other funding streams helps to avoid climate finance just supporting an ongoing series of one-off pilots. For example, in Ghana, four health facilities used grants from climate funds and ongoing revenue from carbon markets to leverage finance loans and private investments. This provided a sustainable source of revenue for both a stand-alone solar system and ‘electric mobility’, using low-maintenance electric motorbikes equipped with chiller boxes to improve the vaccine cold chain, so improving the quality and resilience of health services.

Lastly, the role of health sector budgets in climate resilience should not be ignored. Even if health budgets are unable to stretch to cover additional costs, there are likely to be adjustments to current spending that could deliver significant health and resilience benefits. This is why OPM and others are promoting climate budgeting (see our 2021 policy paper), to understand what climate benefits health sector budgets are already providing and whether and how these can be maximized.

Coming back to the original question, climate finance can make a contribution to health systems strengthening. It can certainly complement health financing, but there is no easy funding tap to turn on. Nor will climate finance be a substitute for proper health sector funding. Climate finance needs to be aligned to the right objectives to be successful, scalable and sustainable. Finally, securing climate finance at scale for the health sector is not an easy or quick fix: it will require significant and sustained collaboration between climate and health experts and government ministries.

These and other learning insights will be further developed by OPM and the ReBUILD partners. We welcome contributions to the discussion to share questions or experience in using climate finance for building health system resilience.

For more information and follow-up, contact Elizabeth Gogoi and Phil Marker.

Further information

Video: Watch the recording of this webinar here

Slides: Read the slides from this webinar here

Policy brief: Strengthening climate-resilient health systems: opportunities and challenges

Image: Bangladesh – Flooding, 2019 – UN Women/Mohammad Rakibul Hasan via Flickr [opens new tab] CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED