Health services and system challenges to people with disabilities (Kuper H. and Heydt P, Missing Billion Initiative)

How can we conduct disability-inclusive health system research?

17 March 2021

Dr Wesam Mansour and Obindra Chand of the ReBUILD for Resilience consortium’s Gender Equity and Justice Working Group reflect on the recent webinar on developing disability-inclusive health system research. If you missed the webinar watch it here.

People living in Fragile and Shock Prone Settings (FASP) are often subject to violence, physical injuries and forced displacement, particularly in armed conflict areas. Such challenges can be amplified for people with disabilities (PWDs) who often also suffer neglect in the humanitarian arena, with limited access to food, water and sanitation, and routine healthcare services. This brings additional challenges to everyday life, increases social distress, creates adverse impact on personal health and hygiene, and ultimately negatively impacts on the wellbeing of PWDs. This occurs primarily in low-resource settings, where health care services and health systems are largely inaccessible for PWDs.

With an ultimate aim of producing scalable health systems research and improving access to and utilisation of equitable healthcare for all in FASP settings, the ReBUILD for Resilience consortium (ReBUILD) recognises that there are historic problems with producing disability-inclusive health system research. The team is committed to addressing these problems by learning through dialogue with others. The webinar participants discussed ways to do health systems research that better meets the needs of PWDs. The overarching objective for the session was for ReBUILD to learn how to research in a disability-inclusive manner and understand how we can inform and enhance global research uptake around disability-inclusive healthcare access in FASP settings.

We benefitted from an experienced and diverse panel that included:

• Professor Hannah Kuper – London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK

• Dr Nukhba Zia – Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA

• Aicha Benyaich – International Committee of the Red Cross, Lebanon

• Deepak Raj Sapkota – Karuna Foundation, Nepal

• Dr Laura Dean – Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK

• Janet Price – a UK-based feminist disability campaigner

The panelists discussed health systems and disability in FASP settings and challenges and key interventions to develop disability-inclusive health systems research. The discussion was structured around three questions:

1. Why is work on disability and health systems so often siloed?

2. Are there any particular challenges in working on disabilities in fragile and shock-prone settings?

3. What would you like a consortium like ReBUILD to do differently and what is the best practice to follow?

The issue of disability in FASP settings is often siloed

All panelists highlighted the problems faced by PWDs. Most of the world’s PWDs live in the global South, often with very limited facilities to help them in their everyday lives, and a significant proportion of those in FASP settings experience disability; indeed, physical disabilities are also often a consequence of living in conflict-affected settings (see footnote 1). As well as experiencing the same malnutrition, gender-based violence, poverty, disease and poor access to healthcare services as the rest of the population, those with disabilities are particularly impacted by living in FASP settings. PWDs face additional barriers to their mobility, learning opportunities, ability to work or care for themselves and their children, and many other aspects of their lives, which can result in emotional insecurity and mental health problems. Women, children, and older people are among the most vulnerable groups. (See footnote 2)

Unfortunately, PWDs are often excluded from accessing mainstream humanitarian aid and protection due to attitudinal and physical barriers, such as a lack of access to mobility and assistive devices, health services and rehabilitation. Both direct and indirect discrimination occur when PWDs are not included in response efforts and reconstruction following conflict. They often face stigma, enormous isolation, and domestic violence. While all women in displaced communities are often at risk of gender-based violence, women with disabilities experience increased exposure to such attacks. Deepak Raj Sapkota, of Karuna Foundation in Nepal, explained how in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), children with disabilities are also neglected since there are often no effective mechanisms at local levels to operationalise the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) endorsed by the United Nations. According to Dr Nukhba Zia, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in the US, the module for measuring disability in children in LMICs developed by UNICEF and the Washington group (see footnote 3) focuses on children aged 5-17 years old. Consideration also needs to be given to under 5-years children who require specific actions when addressing protection.

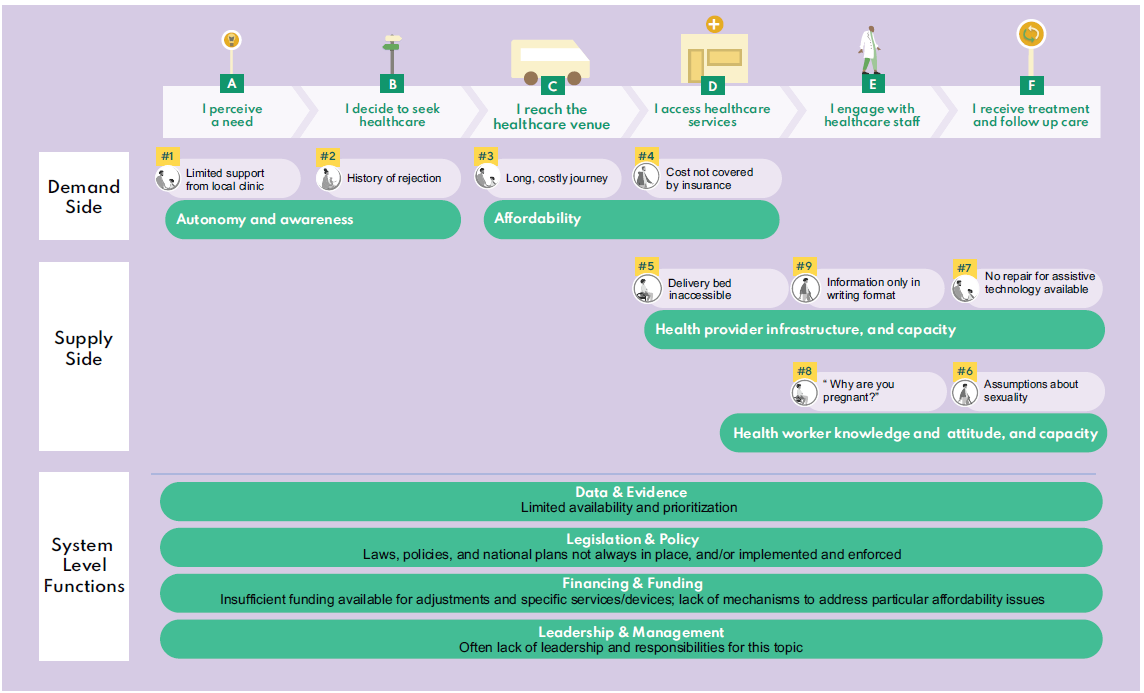

Professor Hannah Kuper, of London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the UK, pointed out that 15% of the world’s population has a disability and these PWDs can experience enhanced health vulnerabilities. The situation is worsened with fragility and shocks. For example, 59% of reported deaths during the COVID pandemic in the UK are among PWDs. PWDs have health needs like anyone else and sometimes also require specialised medical treatment or rehabilitation services. However, as explained by Professor Kuper, across all levels of the health systems, PWDs can face additional challenges. Poor legislation and policy, limited resources, unavailability of data and evidence on the needs of PWDs, and lack of leadership and responsibility are among the challenges that constrain the health system from accommodating PWDs and institutionalising their needs. (See main image and footnote 4)

Policymakers, researchers and activists may be sceptical about including disability in discussions about FASP settings; there are so many urgent and competing priorities for development initiatives in these fragile contexts. However, it is time to recognise PWDs as people with unique abilities who can contribute to social transformation. “A child with a disability can change the community, but it takes a community to raise this child,” Deepak Sapkota said.

Key interventions to promote disability-inclusive health systems research

There are a number of possible interventions, one of which is raising awareness of disabilities which may not be immediately apparent but can still have an impact on people’s lives. Governments, NGOs and humanitarian agencies must take specific actions to include PWDs in their planning and responses. For example, Aicha Benyaich of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Lebanon, described how her team endorses a physical rehabilitation programme involving prosthetics and orthotics services in Lebanon. The programme focuses on the needs of the PWDs, targets areas for development and creates a strategy related to the prosthetic and orthotic sector, facilitating access to mobility aids, devices, and assistive technologies.

PWDs are often excluded from planning and response processes because they are mistakenly considered to be unable to contribute to the transformation process and are often viewed only as victims. Inclusion of PWDs, especially women, in the planning of responses can ensure that their unique abilities are realised and that their needs and rights are considered. Community members, particularl the carers of people with disabilities, need to be also included in order to raise issues of concern to them, as pointed out by Janet Price, a UK-based feminist disability campaigner.

Co-production with PWDs, drawing on critical research methodologies, is critical. Researchers and their peers should involve PWDs in their study designs, listening to their real-life stories, and ensure their critical voices and perspectives are heard. Dr Laura Dean, of Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK, argued that inclusive study design can occur through working in partnership with people with lived experiences and their communities through the use of narrative and participatory methodologies. Also, there is a need for more social science research that understands social and structural pathways to designing health systems that respond to the social and psychological dimensions of people’s lives and successfully mainstream disability, Dr Dean said.

In fact, involving multi-sectoral stakeholders at the national level, including all ministries and policymakers, can help them to appreciate the need to integrate disability into their work. Working with a research team, and including PWDs throughout the research lifecycle, would also help develop a framework and integrate inclusive health system research. In addition, raising disability awareness among policymakers and politicians through campaigns and sharing personal experiences can encourage them to frame disability within the national system and promote mobilisation of resources. In Nepal, the Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation Programme (DPRP) is looking for technical and financial partners to support the roll-out of their existing sustainable and impactful approach for disability-inclusive communities, while the funders look for a high-impact, cost-effective model and seek to support the DPRP replication in other contexts.

Ways forward for the ReBUILD for Resilience consortium

In conclusion, possible routes for ReBUILD to produce more disability-inclusive health systems research are:

• Engagement of PWDs in research design and execution not only makes for better research and increases awareness about issues regarding PWDs but could also contribute to a sense of ownership on the sector/issues.

• Sharing the real-life experiences of PWDs can help influence policymakers and donor agencies.

• Producing data and evidence on the locations and needs of PWDs is vital.

• The dissemination of study outcomes through awareness campaigns and multi-sectoral capacity building, eg inclusive training and mentoring, can help develop disability-inclusive health systems.

• The consortium was encouraged to collect and learn from ‘best-practice’ examples on how to integrate work on disabilities into research, and use these examples as a stepping stone to inform and help design more inclusive health system research.

Finally, we would like to thank our panelists for their great contribution which helped us identify the steps that can contribute to embedding research/evidence in the policy making mechanism, and promote disability-inclusive health system research.

If you missed this webinar, or want to revisit it, you can watch it here.

References

- UN:War’s Impact on People with Disabilities. Security Council Meeting to Focus on Risks, Needs. December 2018.

- Rohwerder B. Women and girls with disabilities in conflict and crises. Institute of Development Studies. Helpdesk Report. 2017.

- Zia, N., Loeb, M., Kajungu, D. et al. Adaptation and validation of UNICEF/Washington group child functioning module at the Iganga-Mayuge health and demographic surveillance site in Uganda. BMC Public Health 20, 1334 (2020).

- Kuper H. and Heydt P. The Missing Billion. Access to health services for 1 billion people with disabilities. 2019.